If you were to analyse the natural and man-made environment, you would soon discover that the simplest object is the dot or point. Small and unassuming, it holds the promise of infinite forms. Stretch it into a line, and it becomes a path, straight or serpentine, threading through space with purpose.

Lines are restless. When they loop and embrace their own tails, they create shapes – creatures of two dimensions. Some mimic nature’s elegance; others are born from human imagination. Shapes that step boldly into the third dimension become solid sculptures, standing firm in their newfound complexity.

Consider the television screen – a modern dynamic tapestry woven from millions of tiny dots. A 4K TV has 3,840 horizontal pixels and 2,160 vertical pixels, rendering a total of about 8.3 million tiny dots that are used to stabilise the images we watch each day.

A single point might seem inconsequential, but it transforms when it joins a grander design. Like a note in a symphony, it finds meaning within the whole. A point stretches to form a line – the simplest journey between two destinations. In art and life, lines build tension, binding points into a frozen dance of geometry.

Nature smiles at straight lines and perfect circles. Her creations sway and curve, driven by unseen forces. Rivers carve their way through earth’s canvas, while leaves unfurl in gentle spirals. Even our bodies favour the grace of arcs over rigid angles.

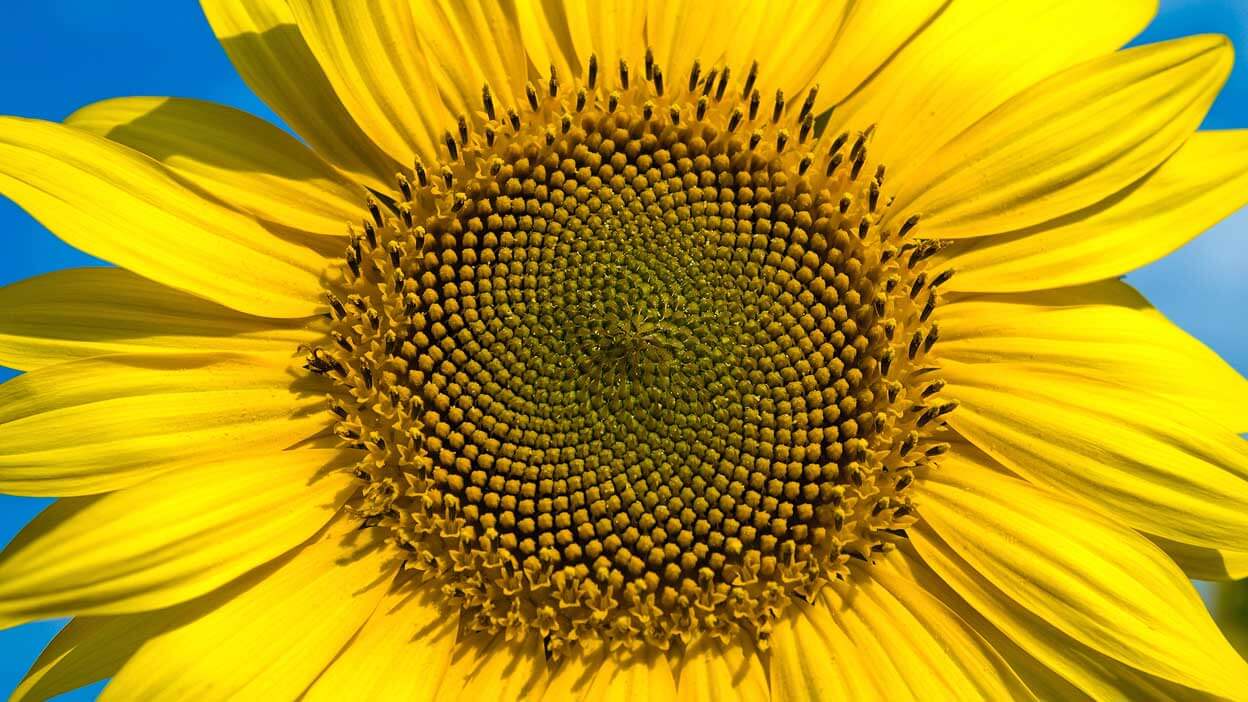

Spirals reign supreme in nature’s kingdom. They spiral outward, like seashells whispering secrets from the ocean floor or trees reaching skyward with wisdom etched in rings. Sunflowers wear spirals as crowns, while the dance of DNA spins life into existence.

In this world of dots, lines, and spirals, we find both order and chaos – an eternal waltz of form and function, of beauty woven into the very fabric of being.

Spirals and Patterns

Not all spirals are the same. The chambered nautilus has an equiangular or logarithmic spiral, similar to a ram’s horns. Sunflowers have a double spiral pattern that matches the Fibonacci Series. If you count sunflower seeds in clockwise and counter-clockwise spirals, the numbers will follow this sequence.

Lines, Shapes and Planes

A line that loops back on itself creates a shape. Lines are crucial for making planes, shapes, and forms. A shape is flat and focuses on area, not volume. When shapes gain a third dimension, they become forms.

Drawing and Planes

In drawings, for example, the paper is the original plane. Other planes can overlap or tilt at various angles. Planes are important in art, architecture, and design, just like lines. They can intersect or stand apart, creating spatial interactions.

Perception of Planes

A plane is the surface of an object and can be flat or curved. It separates and connects design elements. A point or line on paper may seem to lie on, behind, or in front of it. Our eyes perceive these planes even if they aren’t clearly marked.

Shapes and Forms

Shapes start from a point and grow. All forms can be reduced to geometric shapes like spheres, cylinders, circles, or rectangles. The human body, for example, can be seen as a collection of these basic shapes.

Voids and Creation

Voids exist where shapes, planes, and forms do not. The absence of creation is as important as creation itself. Success often depends on deciding what not to create.

Organic Shapes

These are spontaneous, growing forms invigorated mainly by their non-compliance with geometry. They are active, dynamic, free flowing and informal, completely shorn of the rigidity inherent to geometry. Organic shapes resemble forms and actions around us – vegetable, animal and human shapes and happenings, fragments, signs, symbols, silhouettes etched in memory and saturated with all kinds of feelings and associations. They could be connected or unconnected, surrounded with much or little space. They could range in quality from large to small, solid to hollow, with neat or frayed edges.

Geometric Shapes

Squares, rectangles, circles, triangles and all polygons constitute geometric shapes. These forms are geometric derivations, inorganic and synthetic substances, never seen in nature.

Colour

Just as there are audible lowest and audible highest sound frequencies (audible to the human ear), there is a spectrum of colours visible to the human eye. We cannot perceive colours whose wavelength is less than that of red, or more than that of violet.

It is also important to note that while the human eye has its own limitations in perceiving colours, the human brain does not have a very strong mechanism to memorize colours. So, we try to remember colours along with their associations – for example – the red of chillies and of strawberries, of blood and of the hibiscus, of tomatoes and of the Coke logo – and this helps to a certain extent in our understanding of colours, but unfortunately not many people can reproduce the exact colours. It is only when these various reds are simultaneously exhibited before us that we can differentiate between them.

The eye, the optic tract and centres of vision in the brain translate electromagnetic energy, i.e. the light into electrochemical energy via the rods and cones, which are the photoreceptors in the retina, where the cones are the receptors for colour. These complex processes may be simplistically explained as “encoded impulses” being received by the sight centres of the brain. These subtle facilities also transform a multitude of stimuli into meaningful unities or precepts. It is this – the ordering, abstracting and translating of optical data – that commands special attention; for it and the reservoir of experience and memory, underlie all image making.

The psychological qualities of colours are of a more subjective nature and hence do not have absolute values; however, there is a universal acceptance about light and dark colours, or strong and weak colours. We describe some as warm and others as cool colours, some as earth colours and some as aquatic colours; some as heavy, others as light (in weight); some as moist, others as dry. Some colours tend to advance, while others tend to recede; some appear opaque, while others appear transparent.

Absolutely pure hues are encountered less often in nature than one would expect. When they are found, for example, in certain flowers and insects, in certain tropical fish, in bird plumage, moths and butterflies, in certain gem stones, in a rainbow or in a spectacular sunset, they do seem to conform to the natural scale of chromatic values. In a sunset, one sees a gradual movement of colour down the natural order, from golden yellow to orange, to red, to crimson, to a greyed violet-blue, and finally to nightfall. In autumn, the green leaves of trees first turn a singing yellow, then a kind of orange, to an assortment of reds, to crimson, and then, to a rich purple-brown.

Natural, or white light is the result of a combination of all colours in the rainbow: violet, indigo, blue, green, yellow, orange and red – the seven principle colours which the human eye can perceive; before violet are the ultraviolet rays and beyond red, the infrared rays – neither of which are visible. An absence of colour gives black, which, in this sense, means darkness or night.

Form

The commonly accepted definition of form refers to the visual and physical structure of an object. Form is three-dimensional. A fundamental fact of human existence is that we live in a three-dimensional space surrounded by stationary or kinetic forms.

When space appears to be excluded from the form – when length, width and thickness or height is near equilibrium, a solid form exists. A solid form is defined by the space around it. It maintains its numeric thrust against its environment despite incursions in a few shallow areas. It may exist as a monolithic form, a uniform mass not penetrated by space, or one having convex or concave areas, where the proportion of mass is greater than the space penetrating the form.

Geometric Forms

Derived from geometry, these are completely manmade and artificial forms, having very well defined and sharp edges.

The word ‘geometry’ provides a clue to its origin and use: geo – land and metry – measure. Traced back to the ancient Egyptians, they used it in the great engineering and building projects of the Pharaohs, and in the priestly art of numbers and astrology. But the ingenious device of the knotted cord (which led to a way of finding a right angle as a component of a right angle triangle, making it possible to calculate nearly all shapes and sizes of arable land) actually evolved from the problem of land measure that arose every year because of the flooding of the Nile Valley, and the Egyptian practice of levying taxes according to the extent of land ownership. In the sixth century B.C, the knotted cord and triangle idea was brought to Greece.

Geometry, to the Greeks, was a divine exercise, an absolute and perfect way to create designs applicable in the building of temples, making pottery and statues of gods and heroes, and speculating on the essence of matter or the movements of celestial bodies.

Organic Forms

These forms bear close resemblance to vegetable, animal and human forms and materials. They involve growth and they represent change. They are compact, inward, secretive and they tend to be closed in whole or in part; they resist damage by distributing pressures broadly and evenly. They usually represent mass and weight and therefore displace space rather than accommodate space. They tend to be quite durable, regardless of their material substance.

Natural Forms

These are supple and sensitive forms, which tend to merge with the surroundings, rather than stand out and assert their positions. They follow the gentle, free-flowing ways of nature, whereby they neither look predetermined, nor as afterthoughts. They are defined by their gracefully curving, rounded edges.

Space

In a sense, even the most complex form can be seen as a juxtaposition of planes, shapes and the space around or within.

The concept of space, as put forth by Jacob Van Uexküll, a Baltic German biologist who worked in the fields of muscular physiology and animal behaviour studies and was an influence on the cybernetics of life, goes thus: “Like the spider with its web, so every subject weaves relationships between itself and particular properties of objects; the many strands are then woven together and finally form the basis of the subject’s very existence”.

Most of man’s actions comprise a spatial aspect, whereby he relates to the objects of orientation such as inside and outside, far away and close by, separate and united, continuous and discontinuous, above and below, before and behind, right and left. These terms have direct reference to man himself and his position in the world.

The most intangible of all aesthetic elements, space is also the most important one. Whether a small two-dimensional composition or a large three-dimensional structure, the spatial aspect must be studied thoroughly and used sensitively.

Human beings, like all objects, exist in a form-space relationship. Form cannot exist without space, and space is an aid to the perception and appreciation of form. However, by and large, people fail to visualize and comprehend three-dimensional forms, and find it simpler to analyse two-dimensional images to three-dimensional forms, or vice versa.

The Golden Ratio

The unconscious search for relationships that are neither so well balanced as to be dull, nor so precarious as to be irritating, seems to be the basis of the Golden Ratio. This kind of division is neither too difficult to grasp spontaneously, nor too easy to exhaust. Equilibrium is threatened, but a kind of dynamic tension arises that is curiously binding.

The term was given in the nineteenth century to the proportion derived form the division of a line into what Euclid called “extreme and mean ratio” – according to which “a straight line is said to have been cut in extreme and mean ratio when, as the whole line is to the greater segment, so is the greater to the less”.

Most attempts to explain the origin of the Golden Ratio trail off into legend and speculation. Some say it originated in Egypt, others trace its roots to Greece, to the work of certain geometrists like Pythagoras and Eudoxus, both of whom knew Egyptian achievements well. Pythagoras believed that one could demonstrate order in the universe by expressing all relationships among the parts of things in terms of single whole numbers; he believed that such relationships do exist among the perfect intervals of tones produced by sounding a stretching string. Eudoxus is said to have carried with him at all times a stick, which he asked friends and acquaintances to divide at whatever point they sensed to be the most pleasing. Much to his satisfaction they chose more often than not, the point of the Golden Ratio. Fact or fiction, this tale illustrates something important in art and design: the close relationship of intuitive perceptions or felt ratios to reasoned or mathematical ratios.

The Golden Ratio appears in nature showing that this magical number represents the right answer for finding the optimal solution to many covering problems.

In order to create our reality – to make things happen in our experience of the world – we operate at all levels of our being: the spiritual, mental, emotional, physical. We do this 100% of the time whether we are aware of it or not. It is possible to improve our life experience by becoming more conscious of our creative process.

In Western culture, we are brought up to view our lives as primarily a physical manifestation: we go to work, produce things, get paid, survive, try to keep our bodies healthy, find a partner, make a family home. Talk of “creating our reality” from a spiritual viewpoint seems out of touch with reality, maybe even a bit crazy. But if you follow it through – as I will try to explain – it does all tie together.

The everyday life we experience is very much affected by our spiritual nature, our creative will. Then we manifest that “will” according to the beliefs we hold, the feelings that result from those beliefs, and our resulting actions.

We can start living consciously by manifesting what we want right here and now, by putting into place our plans and dreams in the real world.

The first step is to become clear on what you want to create – to decide what you want.

The second step is to visualize, with emotion, it happening – until you get to a point where you know it already has happened and is on its way to you.

The third step is to be open for guidance, from the source of knowing that you are spiritually connected to and part of. Wait for spiritual guidance before taking action. If you take action before receiving guidance you may end up running into blocks or manifesting something other than what you really want.

Spirit-mind-emotions-body-the world: this is a circle, a wholeness. We are all connected. Because spirit is of the nature of information, not within the boundaries of space and time, the beliefs of a few conscious beings influence the group consciousness of Mankind – or perhaps I should say group unconsciousness, since relatively little conscious will is expressed here, but the unconscious still responds. I feel the current state of the world is a wake-up call and things are changing; there could be an exponential increase in the expression of our true nature, of Love, in our world. It is up to each of us to play our part.

Enhance Emotional Literacy

Feelings are a complex aspect of every person. While research has identified eight “core” feelings (fear, joy, acceptance, anger, sorrow, disgust, surprise, anticipation), we each experience dozens, even hundreds, of variations each day. These emotions blend and merge, and frequently they conflict. This EQ fundamental helps us sort out all of those feelings, name them, and begin to understand their causes and effects. It also helps us understand how emotions function in our brains and bodies, and the interaction of thought, feeling, and action.

Recognize Patterns

The human brain follows patterns, or neural pathways. Stimulus leads to response and, over time, the response becomes habitual as the pathway becomes a road, the road a highway, and the highway a super expressway. Then it requires extraordinary measures to interrupt the established habit. The patterns include thinking, feeling, and action in a continuous cycle.

At a young age, we learn lessons of how to cope, how to get our needs met, and how to protect ourselves. These strategies reinforce one another, and we develop a complex structure of beliefs to support the validity of the behaviors. Often this system of patterns serves us well, and at other times it leads us to unconsciously create the opposite of what we really want.

The core skill of emotional intellence (EQ) is remaining truthful with oneself; from this develops integrity and personal authenticity. Insight techniques take “knowing oneself” still further, to ever deeper levels. Where one is no longer wearing masks or running from shadows, one discovers the true spiritual identity, the Higher Self.

In Latin, the word emotion means “the spirit that moves us”.

The source of that energy is YOU!